From Newton and the Three-Body Problem to Chaos: How Scientific Understanding Evolved from Simplicity to Complexity

Modern science began with Newton, who was an extraordinary scientist. As is well known, he discovered the law of universal gravitation and Newtonian mechanics, and was also one of the co-founders of calculus. Few people can compare to Newton in terms of contributions to science. If a person accomplished just one of these achievements in their lifetime, they would be considered a great scientist, yet Newton achieved all three.

There is a well-known legend about Newton: while he was taking a nap, an apple fell on his head, which inspired him to develop the theory of universal gravitation. This moment is often considered the origin of modern science. My alma mater, Nanjing University, once received seeds from the apple tree in Cambridge University, England. If you want to see the descendants of the very apple tree that fell on Newton, you can visit the new campus of Nanjing University.

There is a funny joke in this cartoon, which goes something like this: “I think the more difficult thing is how to apply for research funding. After all, I can’t expect to get funding just because an apple fell on my head.”

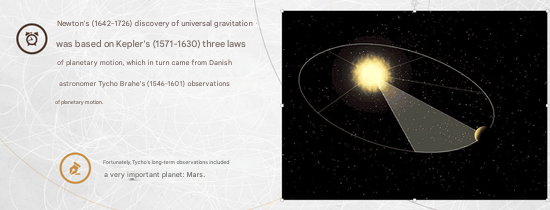

You might think that Newton’s discovery of gravity was a lucky accident, but in fact, it was not. The law of universal gravitation was the result of many years of observations made by predecessors.

A similar example is Kepler’s discovery of the three laws of planetary motion. (Editor’s note: The laws are: 1) The Elliptical Law: All planets orbit the Sun in ellipses, with the Sun at one of the foci. 2) The Area Law: The line connecting a planet to the Sun sweeps out equal areas in equal time intervals. 3) The Harmonic Law: The square of a planet’s orbital period is proportional to the cube of its average orbital distance from the Sun.) Kepler’s three laws were also not discovered by accident or sudden inspiration.

The first scientist in history to die from holding his urine: Tycho Brahe

Before Kepler discovered the three laws of planetary motion, there was a Danish mathematician, Tycho Brahe, who spent a lot of time observing the motion of planets. At that time, the observational accuracy was poor, and he had to observe the planets with his naked eye, which required a great deal of effort.

The Danish emperor even funded the construction of an observatory on an island, spending a lot of money to support his research. Interestingly, the paper he used to record his observations was supplied by a specialized paper mill.

Tycho had a good relationship with the emperor, but after the emperor’s death, the new ruler didn’t like him. He then moved to Prague, where the emperor there was very supportive of his scientific research, allowing Tycho to frequently visit the palace. One time, after drinking a lot at the palace, he returned home and died. People speculated about the cause of his death: one theory suggested poisoning, while another guessed he died from holding his urine. Over four hundred years later, in 2001, someone decided to exhume his body to determine the cause of death. It turned out that he wasn’t poisoned but had indeed died from holding his urine. Tycho became the first scientist in history to die this way.

Ten years later, another major controversy arose regarding Tycho. Tycho had an eccentric personality, and in his twenties, he argued with his cousin about who was the greater mathematician. They decided to settle the dispute with a duel, during which Tycho’s nose was severed. For a long time, people wondered whether his nose was made of gold or silver. In 2010, they decided to exhume his coffin for further study, and it was discovered that his nose was actually made of copper.

Tycho’s observations laid the foundation for Kepler’s work and for the beginning of the law of universal gravitation. As his student, Kepler observed the motion of Mars. If Mars had not been observed, people would have believed that planetary orbits were circular. It was through these observations that Newton was finally able to discover the law of universal gravitation, and it wasn’t just because an apple fell on his head.

The three-body problem cannot be solved using classical methods.

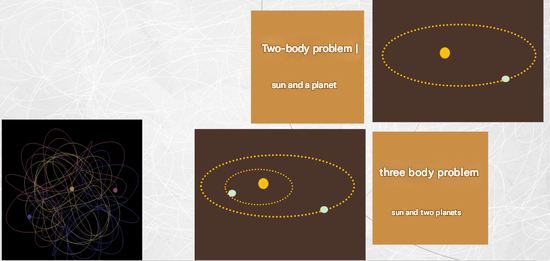

When Newton discovered the law of universal gravitation, the first problem he sought to solve was the many-body problem. With universal gravitation, Newtonian mechanics, and calculus, this astronomical problem became a mathematical one.

How to use these physical laws to find the orbit of a planet and precisely calculate its path? When the Sun and a planet are considered together, it’s a two-body problem, and we know that the orbit in the two-body problem is stable. However, when the Sun and two planets are considered together, it becomes a three-body problem. The more celestial bodies involved, the more complex the mathematical problem becomes. The three-body problem took a long time to study, and ultimately, people discovered that it is unsolvable.

The solar system is far more complex than a three-body problem. It involves the Sun, planets, moons, and many other small celestial bodies. The entire solar system is a massive system, far exceeding the complexity of the three-body problem, making it a much more complicated multi-body problem. Since the three-body problem is unsolvable, it’s clear that using classical methods to solve the motion of the solar system is also highly unlikely.

It’s also worth mentioning Newton, who was another “eccentric” figure. In his earlier years, he made incredibly important contributions to science, but he was also a very devout Christian. He believed that the solar system was unstable. People would ask, if the solar system is unstable, how could humans possibly survive? Newton’s explanation was that God would periodically give the planets or spheres a little “push” to bring the Earth back onto a stable orbit, preventing it from drifting too far off course.

Newton constantly tried to use mathematics to prove the existence of God, attempting to solve the planets’ orbits with mathematical formulas. In hindsight, this seems rather absurd, so some joke that after the apple fell on Newton’s head, his brain wasn’t quite the same.

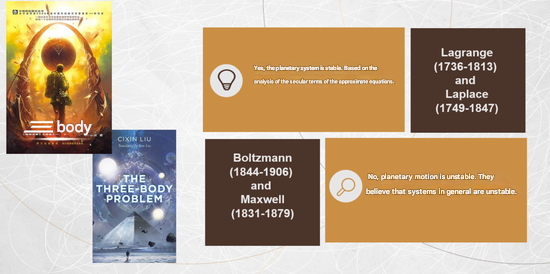

Every great scientist has offered their own insights into the stability of planets, sometimes based on mathematical analysis, and other times more on conjecture.

Why is the novel “The Three-Body Problem” so interesting?

Everyone knows that mathematicians enjoy making conjectures, like in the classic science fiction work The Three-Body Problem. Why do people find this novel so interesting?

I just mentioned that the three-body problem cannot be solved using classical methods. The three-body system is a chaotic system, and its most important characteristic is unpredictability. The motion of the three bodies, if observed for not enough time, makes it impossible to predict how things will change in the future. The novel The Three-Body Problem uses this characteristic to describe a world with three suns, where their orbits are in a highly unpredictable state. Sometimes, all three suns might suddenly appear, causing all life on the planet to burn up. Other times, all three suns might disappear for a period, making the planet very cold and freezing all life. This is the scientific principle behind the novel The Three-Body Problem.

For humans, there’s no need to worry about the stability of the solar system. Scientists have calculated that there’s no issue for millions, or even billions, of years. Even if it becomes unstable, such changes wouldn’t occur for several billion years.

Why should humanity care about the stability of the solar system? I would say that the development of science doesn’t start from a practical perspective. Modern science stems from Newtonian mechanics, which in turn comes from celestial mechanics. Initially, celestial mechanics satisfied human curiosity. However, science, unlike technology, brings revolutionary changes to human life. Technology is competitive, while science is revolutionary. Everything in modern life is a result of scientific progress, so it is wrong to view scientific research through a utilitarian lens.

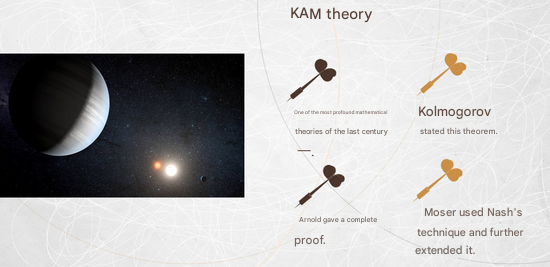

Mathematicians have a profound theory called the KAM theory (Editor’s note: The KAM theory is a famous theory in classical mechanics that discusses nearly integrable conservative systems: Hamiltonian systems, reversible systems, and volume-preserving dynamics. K, A, and M represent the three mathematicians who established this theory in the 1950s and 60s: Russian mathematicians Kolmogorov and Arnold, and German mathematician Moser). Many mathematicians have made significant contributions to this theory. One of the key concerns in mechanical systems is the long-term behavior of the motion process and the state it will eventually reach. The long-term behavior of a dynamical system can take various forms: equilibrium or fixed points, periodic oscillations, quasi-periodic motions, and chaos, all of which are steady states.

Newtonian mechanics’ deterministic view dominated for a long time due to its success in solving the planetary motion problem in the solar system. However, the three-body problem in mechanics and the motion of rigid bodies around fixed points became challenges that troubled people for nearly a century. The KAM theorem, by proving the stability conditions for the motion of weakly non-integrable systems, demonstrated the universality of chaotic behavior in the trajectories of nonlinear systems with more than three dimensions.

The opposite of stability is chaos. With the progress of cognition, we have come to realize that the world is increasingly diverse, and the possibility of stability is becoming less likely. In most cases, systems are dynamically stable or chaotic.

Poincare: The first scientist to describe chaos

The image above is of King Oscar II of Norway, the only emperor who was also a mathematician. He studied mathematics as an undergraduate and had a strong passion for science and art, regularly organizing scientific lectures at the royal palace. During his reign, he founded a mathematics journal, Acta Mathematica, which is still one of the four major journals in the field of mathematics today.

In 1887, a mathematician named Mitag Lefler suggested that King Oscar II establish a scientific prize for anyone who could solve the three-body problem. Although we now know that the three-body problem is unsolvable, at the time, it was not known.

Who was Mitag Lefler? Let me tell you a story about why there are no mathematicians among the Nobel Prize winners. The legend goes that Alfred Nobel’s lover was seduced by a mathematician, and that mathematician was Mitag Lefler.

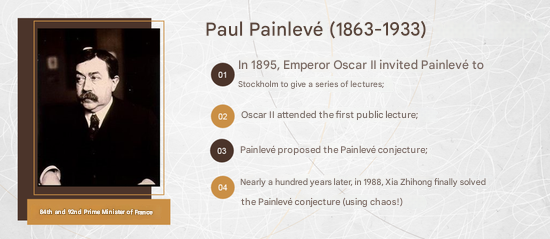

In 1895, the emperor invited the mathematician Painlevé from the University of Paris to give a lecture at the palace. During the lecture, Painlevé proposed a conjecture, now known as the Painlevé Conjecture. Less than a hundred years later, it was solved in my doctoral dissertation using chaos theory.

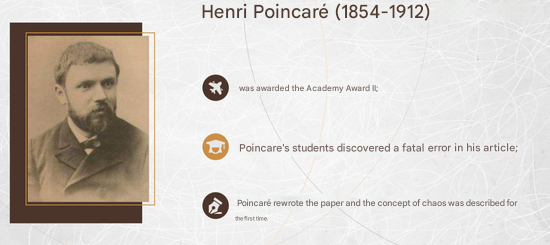

You might wonder why it took so long. The reason is that our understanding of science develops step by step. Poincaré and Painlevé were contemporaneous mathematicians, and the conjecture I proved was one that they had discussed together. Poincaré wrote a paper on how to solve the three-body problem, but although he didn’t find a solution, the award committee still decided to give him a major prize. Interestingly, however, his student later discovered errors in the paper. Poincaré then rewrote the paper, and in it, the concept of chaos was correctly described for the first time in mathematics.

The most basic concept of chaos: geometric growth rate is extremely fast

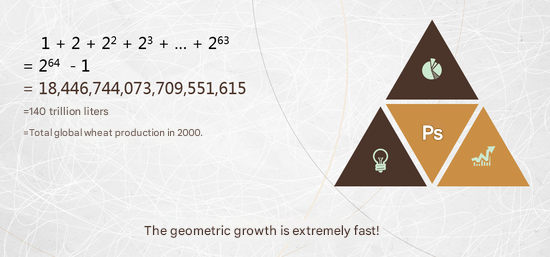

This story is likely familiar to many. A mathematician invented chess, and the emperor, very pleased, asked him what kind of reward he wanted. The mathematician said simply, “Place one grain of wheat on the first square, two on the second, four on the third, eight on the fourth, and so on, doubling each time, until the entire chessboard is filled.” The emperor thought the mathematician’s request was modest—just a few grains of wheat—and agreed immediately. But how many grains of wheat were actually needed? There are 64 squares on the chessboard. The first square has 1 grain, and the last square has 2 to the 63rd power. In total, the number of grains needed is 2 to the 64th power minus 1, which is roughly 140 trillion liters of wheat. This illustrates how rapidly exponential growth increases, and it’s one of the basic concepts in chaos theory.

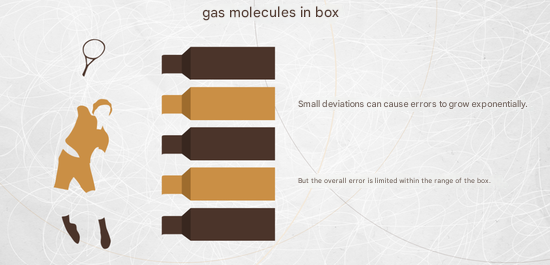

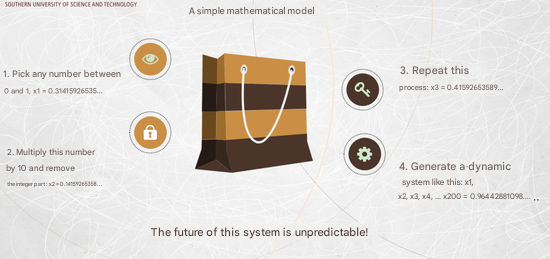

Look at the box in the image. Suppose we place gas molecules inside; these molecules move at extremely high speeds. If there is even a tiny initial error, it doubles in the first second, doubles again in the second second, and continues doubling in the third second. After 60 seconds, the error has grown by a factor of 2 to the power of 60. No matter how small the initial error was, it will have been magnified enormously through this process. This illustrates the significant consequences of molecular motion. The extent of chaos depends on how frequently this doubling occurs over time.

In aerodynamics, air moves quite rapidly, and errors can double in just fractions of a second. In contrast, the motion of the solar system is much slower—an error might take decades or even centuries to double. However, they share a common characteristic: the error keeps doubling over time. As time stretches further, it becomes impossible to trace the system back to its original state because the cumulative effect of repeated doubling makes the future fundamentally unpredictable. This is the principle of future unpredictability.

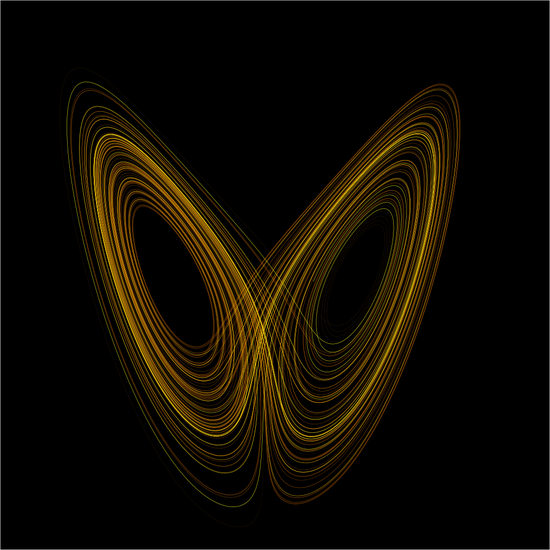

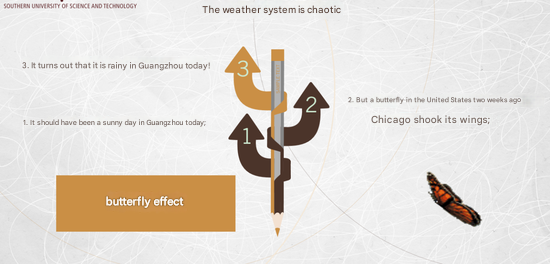

The weather system is one of the most typical chaotic systems. Many people have experienced this: planning a weekend trip based on a forecast of sunny skies, only to find it pouring rain when the weekend arrives. It’s common to blame the meteorological office for inaccurate predictions, but in reality, weather is an extremely chaotic system, making long-term forecasts nearly impossible. For instance, Madagascar might be expected to have clear skies, but if a butterfly flaps its wings in Chicago, the disturbance in the air could double within a second and, two weeks later, influence the weather in Madagascar.

This is the butterfly effect, which explains why the weather system is a classic example of chaos. To make precise weather forecasts, you would need to know what every butterfly in Chicago did two weeks in advance. However, there are many other factors with an even greater impact, such as cars, airplanes, and human activity. Predicting the climate in Madagascar two weeks later would require knowing everything happening on the other side of the planet—an almost impossible task. This is why short-term weather forecasts are feasible, but long-term forecasts can only be made in terms of probabilities.

Is chaos good or bad?

Everyone knows that chaos can be extremely unpredictable, but does that necessarily mean it’s a bad thing? Let me give you an example where a chaotic system is actually beneficial. Countries like China, the United States, and India are all actively pursuing space exploration, aiming to reach the Moon and Mars. As a result, they need to launch numerous satellites and probes.

In April 1991, Japan launched the Hiten lunar probe, only to realize after liftoff that it didn’t have enough fuel. You might think such an issue should have been avoided, but the reality is that rocket launches involve many uncertainties. Adding extra fuel increases the spacecraft’s weight, meaning less room for scientific instruments. While the fuel was carefully calculated to be just enough, unexpected circumstances led to a shortage. To help solve this problem, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) at Caltech sent a mathematician named Belbruno to assist the Japanese team in redesigning the probe’s trajectory.

The solution was to use the limited fuel to send the probe into a chaotic region, where its future trajectory would be unpredictable and could lead it to various locations. When it reached a favorable position, it could be allowed to continue naturally, while in less favorable situations, a small fuel adjustment could steer it in the right direction. In October 1991, using this method, scientists successfully guided the probe into lunar orbit.

One day, Belbruno called me and said he had read one of my papers. He told me that when he was searching for the chaotic region, it took him a whole month. But if he had read my paper on chaos earlier, he might have found the right region much more quickly. I was thrilled to hear this—I never expected that one of my published papers would actually have a real-world application.

I originally thought that after this incident in Japan, it was unlikely to happen again. But seven years later, in 1998, a probe from Hughes in the United States faced the same problem—it was launched only to discover it didn’t have enough fuel. Once again, they turned to Belbruno for help. He quickly redesigned a new trajectory, allowing the probe to successfully reach its intended orbit.